Biography on George Washington Maher from the book “Pleasant Home: A History of the John Farson House,” written by Kathleen Ann Cummings

Biography on George Washington Maher from the book “Pleasant Home: A History of the John Farson House,” written by Kathleen Ann Cummings

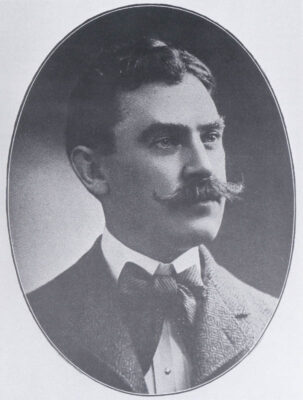

The Architect

Born in Mill Creek, West Virginia on December 25, 1864, George Washington Maher was the son of Sarah Landis and Theophile Maher. His family moved to New Albany, Indiana where Maher was educated in the public schools. First listed in city directories in 1883 as a draftsman for the Chicago architects Augustus Bauer and Henry W. Hill, Maher left their office by 1887 to take a position with architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee. There he worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, George Grant Elmslie, and Cecil Corwin. While his announcement of an independent practice came in late 1888, Maher shared an office and periodically collaborated with Corwin from 1889 until 1892.

In the early 1890s George Maher’s independent practice largely consisted of designs for houses and apartments in Chicago and its early suburbs. On Chicago’s south side Maher built a shingled, colonial revival house (1889) which he shared with his parents. Commissions for houses in Oakland and Kenwood came with the surge of construction surrounding the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893). The Dau House (1896) in Kenwood with its hipped roof, simplified openings, and cubic massing precedes Pleasant Home’s design by only a few months. Maher’s mature Prairie School design, the Ernest Magerstadt House (1907), is also in Kenwood.

George Maher’s work is best preserved today in Kenilworth, Illinois in Chicago’s north shore. Maher married Elizabeth Brooks, daughter of the Chicago artist Alden Finney Brooks, and settled there in 1894 with a Queen Anne house for John Scales, the street’s developer, Maher continued to work in the neighborhood over a twenty-year period. Some of his finest buildings are preserved there: the Sullivanesque Edwin Mosser House (1902) as well as the Prairie style designs for the William Lake House (1904), the Grace Brackebush House (1909), and the Claude Seymour House (1913).

His Work

His early work in Chicago and Kenilworth brought Maher to the forefront of residential design. The commission from John Farson for Pleasant Home initiated a new period in his work. After 1900 came a series of grand houses set on large estates often decorated by the Midwest’s finest artists and craftsmen. Some of these have been demolished: the Arthur B. Leach House, South Orange, New Jersey (1899) for Farson’s partner; the James Patten House, Evanston, Illinois (1901); the Harry Rubens House, Glencoe, Illinois (1903); and Rockledge, the summer house for Ernest and Grace Watkins King in Homer, Minnesota (1911). Pleasant Home and the Frederick Gates House in Montclair, New Jersey (1902) are the only surviving examples on this scale. In each of these estates, Maher used his personal design philosophy which he called motif rhythm theory. The motifs or patterns that Maher repeated in his decoration were luxuriant flowers such as the thistle, the poppy, and the lily that he combined with geometric shapes: circles, squares and stars. Maher’s collaborative work with artists like Louis Millet, Willy Lau, Giannini and Hilgart, and the Tiffany Studios in making stained glass, mosaics, textiles, and furniture for these houses produced some of the most highly crafted examples of arts and crafts design in America. Many of these objects now are in museum collections.

After 1900 Maher began to explore stucco as a new building material. Modest suburban houses built before 1910, including the Corbin House, the Lackner House, and the Ely House in Kenilworth; the Erwin House in Oak Park; the Schultz House in Winnetka; and the Blinn House in Pasadena, show how Maher treated the material sculpturally, often using battered walls and piers at the entrances and swelling forms for balconies and porches. Often trimmed with stained wood, these houses fit comfortably into the wooded suburbs surrounding Chicago. Into these landscapes Maher placed pergolas to connect houses with their gardens.

Landscape designer Jens Jensen drew plans for the grounds surrounding several Maher houses and one of Jensen’s earliest residential projects was for the Harry Rubens estate. While plans by Jensen exist for many other Maher projects such as Pleasant Home, the Mosser House, and the Kenilworth Assembly Hall, the character of these landscapes and the extent to which they were executed is only beginning to be studied. Maher took credit for the design of the early gardens at Pleasant Home and later he collaborated with another eminent Prairie style landscape designer, Ossian Cole Simonds, in laying out the town of Kincaid, Illinois (1914).

While Maher is known for his residences, his work included buildings of all types, ranging from the water tower in Fresno, California (1893) to the Cliffs Shaft Mine Headframes in Ishpeming, Michigan (1919). For Northwestern University he designed the Swift Hall of Engineering (1907), a campus plan (1907), and the now-demolished Patten Gymnasium (1908). The commercial buildings in Winona, Minnesota are important Prairie School works. In 1911-12 Maher designed the administration building for the J. R. Watkins Medical Company as he had underway Rockledge, the house for Ernest and Grace Watkins King. Maher’s final Winona commission was the Winona National and Savings Bank, opened in 1916 after a long period of design and construction. Maher claimed that his revised plan represented a new and American idea in banking.

A prolific author, George Maher wrote as early as 1889 about the need for a new American architecture, and throughout his career he continued in his writings to encourage other architects to develop an indigenous style based upon local conditions. His work is allied with the progressive architects in Chicago who developed a new approach to design free from historical references. Maher and his contemporaries, now known as the Prairie School, embraced many of the ideals of the arts and crafts movement: truth to materials, a belief in fine craftsmanship, and a desire to incorporate the local environment in their buildings and its details. One of the places where Maher could share his beliefs was at the Chicago Architectural Club. As a member, he showed his work on a regular basis at its spring exhibitions and often served on its juries. In 1901 Maher was elected to the American Institute of Architects, this country’s professional organization for architects, and he received its highest mark of distinction when he became a fellow in 1916. During the early 1920s he acted as chairman of the committee for the restoration of the Palace of Fine Arts from the World’s Columbian Exposition which eventually became the Museum of Science and Industry.

Maher’s son Philip first joined his practice in 1914. After service in World War I, Philip completed his architectural education at the University of Michigan (1918) and re-entered his father’s office. Philip Maher became a partner in the firm of George W. Maher & Son in 1922. In the 1920s the Mahers drew several plans for suburban and community developments. These include projects for Hinsdale, Glencoe, and Kenilworth in Illinois as well as ones in Gary, Indiana, and Saugatuck and South Haven, Michigan.

Maher spent his summers in Fennville, Michigan, and quiet community south of the popular resort towns of Saugatuck and Douglas. By 1910 he built three cottages at Hilaire, as his family named their property on the lakeshore. The Mahers stayed at the bungalow; Elizabeth’s parents, Alden and Ellen Brooks, summered in the cottage; and George’s sister, Mary Maher Hooker, lived across the road at Landis Lodge. Family accounts record gatherings there and tell of Maher’s interests in motoring and fruit farming. They also reveal the intensity of Maher’s work in the 1910s, but by the early 1920s illness periodically prevented him from practice. He died at Hilaire in 1926.